Uber Stock: Price, Earnings, and Outlook

Uber's Q3 Looks Good, But Its Future Value Is Still Driving Through a Fog of Autonomous Uncertainty

Uber’s third-quarter earnings report, dropped on November 4th, presented a picture that, on the surface, looked pretty robust. The firm didn't just meet management’s forecast for 20% bookings growth; it exceeded it. Metrics that typically make investors smile—monthly active platform consumers, trips, trip frequency—are all clocking in at all-time highs and, critically, accelerating. This isn’t a small detail; these are the very sinews of Uber’s vaunted network effect, a phenomenon Morningstar rightly points to as the primary driver behind its narrow moat rating. When more riders mean more drivers, and more drivers mean better service, you’ve got a self-reinforcing loop that's tough to crack.

You could almost feel the collective sigh of relief from investors as those Q3 numbers hit, a temporary respite from the usual market anxieties. Uber’s strategy of "affordability investments" seems to be paying off, capturing demand even in an uneven economic recovery where lower-end consumers are reportedly feeling the pinch. It’s a classic volume-over-price play, and for now, it's working, strengthening the offering. This isn't just about market share; it's about scale, which allows Uber to spread fixed costs across a larger base of trips, creating a tangible cost advantage.

The Autonomous Elephant in the Room

Despite the solid Q3 performance and the undeniable strength of its current network, Morningstar maintains that Uber stock (UBER) is only "fairly valued." Why the hesitation when the numbers look so good? The answer, as it so often is in the tech world, lies in the future, specifically in the looming, nebulous shadow of autonomous vehicles (AVs).

Morningstar, in their assessment, raised their fair value estimate from $90 to $93 per share, largely due to a declining insurance cost curve stemming from a recent legislative victory in California. That’s a clear, quantifiable positive. But here’s the kicker: they immediately balance this out with the "significant disruptive threat" posed by Tesla’s Robotaxis. My analysis suggests this isn't just a balancing act; it's an acknowledgment of a fundamental, almost existential, risk that remains largely unquantified. They project Uber’s revenue to grow about 14% annually—to be more exact, 14% on average over the next five years. I've looked at hundreds of these fair value estimates over the years, and the balancing act here—a legislative win against an existential tech threat—feels less like calculation and more like a hopeful shrug.

Uber's current growth, for all its impressive metrics, feels a bit like a magnificent cruise liner steaming ahead, blissfully unaware that its engine room is being quietly replaced by a potentially hostile, autonomous pilot. Who owns that new engine? That's the billion-dollar question. The long-held goal of an "asset-light business model" for Uber starts to look less like a certainty and more like a wish-list item when you consider the ambiguity surrounding AV ownership. Uber’s belief that private equity will step in to own these capital-intensive vehicles sounds less like a strategic expectation and more like a desperate plea.

Think about it: who actually assumes vehicle ownership in this new AV paradigm? And what happens to Uber's vaunted "network effect" if the very supply side of that network (the drivers, or rather, the vehicles) is no longer under its direct economic influence? The bulls will tell you Uber is perfectly positioned as the demand aggregator, the ideal partner for AV companies looking to scale. The bears, however, paint a starker picture: AV companies, unburdened by driver salaries, will possess a superior cost structure. They could develop their own exclusive applications, effectively cutting Uber out of the lucrative ridehailing market entirely, or at best, relegating it to lower-margin fleet management services like charging and cleaning. This isn't just about competition; it's about a fundamental shift in the value chain, where the economic leverage shifts dramatically.

Morningstar assigns Uber a "Very High Uncertainty Rating," and honestly, that feels like an understatement when you consider the sheer scale of the AV disruption. It's a curious line of reasoning, isn't it, that the proliferation of more AV companies beyond Waymo and Tesla is supposed to diminish Uber’s risks by offering "more profitable partnerships"? My analysis suggests this presumes a highly optimistic scenario where Uber's negotiating leverage remains intact, a presumption not fully supported by the economic realities of a zero-driver cost structure. The new partnership with Toast, clarifying the runway for food delivery growth, seems like a smart diversification, a hedge against the ridehailing uncertainty. But a hedge isn't a solution.

The Unaccounted Variable

Uber’s operating performance, free cash flow, and network effects are undeniably strong right now. However, the company’s valuation remains tethered to a future that is, at best, opaque. The market isn't just buying current performance; it's buying future earnings, and those future earnings in ridehailing are directly exposed to a technological shift that could fundamentally alter Uber's role, its margins, and indeed, its very existence. The numbers today look good, but the biggest variable isn't on the balance sheet. It's on the horizon, driving itself.

Related Articles

Ron Baron: His Net Worth, Tesla Bets, and Investment Strategy

Ron Baron's Tesla Optimus Claims: Genius or Just a Billionaire's Fever Dream? Alright, so I caught R...

Brad Gerstner's Vision for the Next AI Titan: Why AMD's 'Bet the Farm' Move Could Change Everything

Every so often, a piece of news hits my desk that feels less like an update and more like a tectonic...

The VIX Name is a Complete Mess: What the Streaming Service Is vs. That Stock Market Thing

So, the market’s "fear gauge" finally decided to show a pulse. Give me a break. On Friday, the VIX s...

MicroStrategy (MSTR) Stock: Analyzing the Bitcoin Correlation and Its Price Action

The recent price action in Strategy’s stock (MSTR) presents a fascinating case study in market perce...

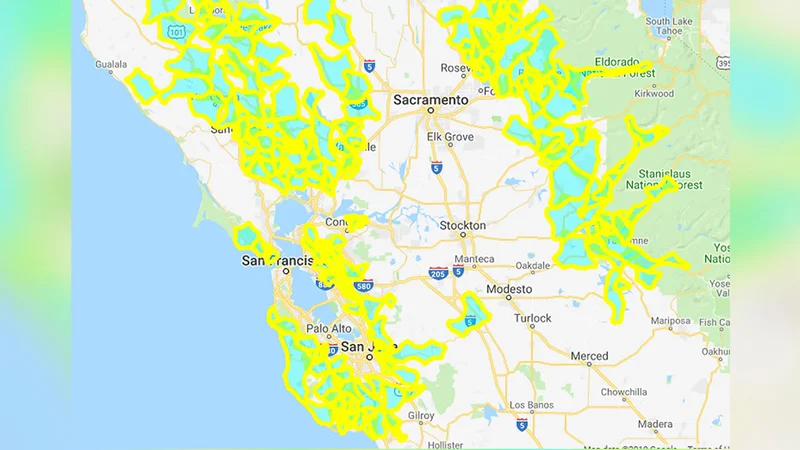

PGE's Landmark Solar Investment: What It Means for Europe's Green Future

Why a Small Polish Solar Project is a Glimpse of Our Real Energy Future You probably scrolled right...

LendingTree's CEO is Dead: Let's Talk About the Real Fallout

The Visionary is Dead. The Press Release Was Ready. One minute, you’re a 55-year-old tech founder ri...